Above: Emma Balder, Harmony, 2020. Recycled fabrics, rope, bungee, paper, acrylic, and thread on canvas, 40 x 81 x 3″. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Jay Marroquin.

By Alexandra Goldman

This month I was excited to be connected for a virtual studio visit with Houston-based artist Emma Balder by my friend, colleague, and mentor, Dr. Jose Falconi, Lecturer of Latin American art at Brandeis University.

Balder was born in Boston in 1990. She grew up curiously watching her mother sew costumes for her and her siblings, and as a young teen experimented with cutting up and sewing her own clothing. She later earned her BFA from SCAD with a background in painting, and has since shifted toward heavily incorporating sewing and fiber art into her practice using recycled materials.

Emma Balder’s studio, Houston, TX. Courtesy of the artist.

She began integrating textile waste into her practice during her formative year-long residency at the Vermont Studio Center, where she was given bags of the recycled scrap cloth material as a gift by a fellow resident who had an excess of it and couldn’t take it traveling overseas. Since then, Balder has continued to collect textile waste from seamstresses and fashion designers. “There is so much waste, and it bothered me, but I saw beauty in it,” Balder noted. Additional examples interesting artists who work with recycled textiles include Tamara Kostianovsky and Linda Friedman-Schmidt. The interpretations of the medium by these three artists is vastly different, showing off its vast potential.

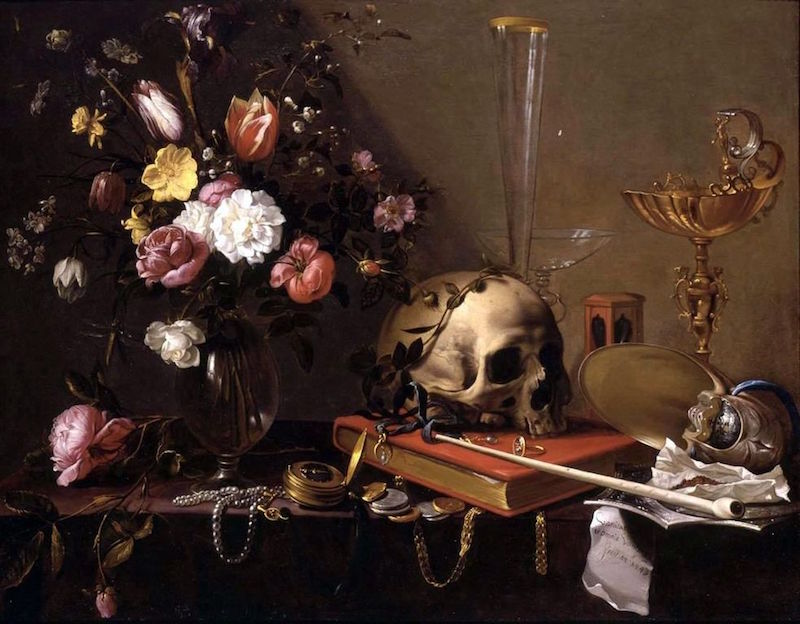

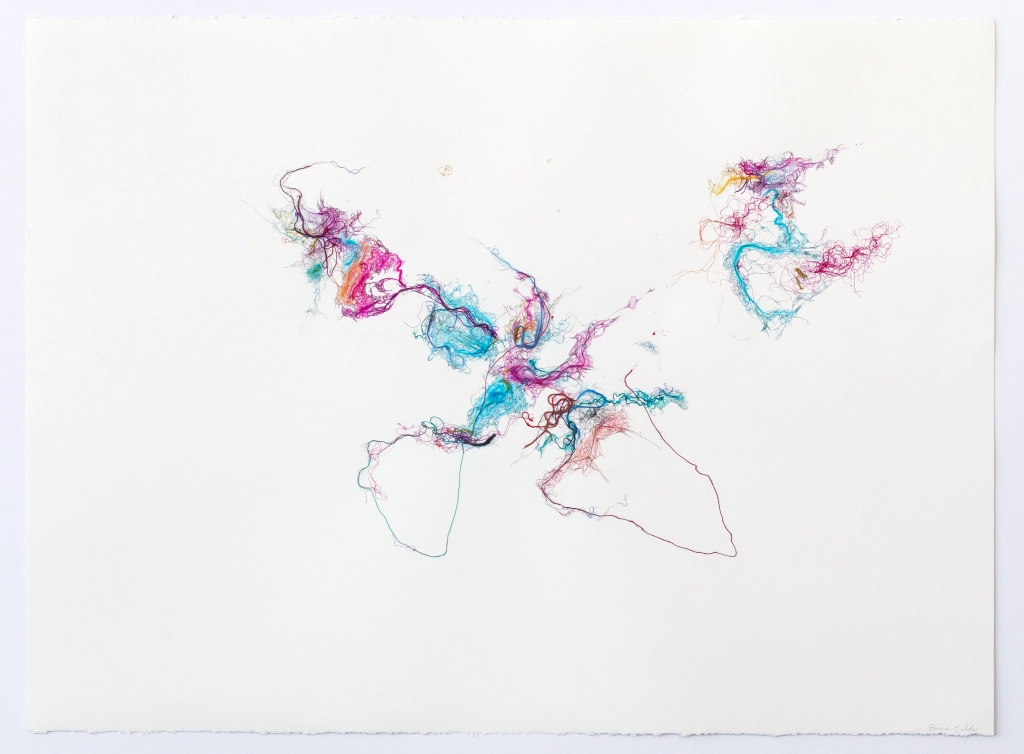

Her colorful organically shaped works fall into two main categories: “Pinglets”, which are (often stuffed) three-dimensional wall pieces that Balder creates by completing a painting, cutting it up, and re-stitching it together in new compositions mixed with other recycled textiles, and “Fiber Paintings”, in which Balder “paints” on paper and panel with colorful thread, using the thread itself as the paint. A fervent environmentalist, working with recycled fiber materials is of utmost importance to Balder.

Emma Balder, Magnet of Hope (detail), 2019. Fibers, graphite, acrylic and micron on paper, 30 x 40″. Photography © Jay Marroquin; Artwork © Emma Balder

On her website, Balder notes, “The Pinglet project documents a process of regeneration. This project began with the physical deconstruction of one painting, the Ping. The disjuncture of parts were then rearranged and reconstructed with needle and thread to form small baby paintings, called Pinglets.” Pings are usually abstract landscapes of around 12 x 8 ft. Balder knows to cut up the Ping at the moment she is satisfied with it, believing the moment that you become complacent, it is time to catalyze change and reignite the creativity that comes from vulnerability.

Following our studio visit I’ve come to understand why Balder has named one of her main artwork styles a made up word such as a “Pinglet”: Balder is principally interested in creating artwork as a manifestation of her own world on her own terms: a place to escape to and live in; both a new world and a new home. In a Derridean sense, this logically begins with creating and defining her own language to refer to her new world without relying on preexisting terms. In her work she creates a beautiful synergy by deconstructing and reconstructing both the physical materials she is utilizing to create the works, and the language she uses to describe them.

Emma Balder, Remains 2, 2020. Fabric, paper, wool, yarn, acrylic and thread on canvas and linen, 29 x 38 x 3″. Photography © Jay Marroquin; Artwork © Emma Balder

Pinglets are filled with vibrant bursts of shape and color caught in a balancing act throughout the composition channeling an unlikely yet successful combination of Vasily Kandinsky and Howardena Pindell. The Pinglets look like stuffed animals in the shapes of clouds, human organs, puddles, or the symbols for hills in Aztec Codices. Balder’s work also visually recalls the legacy of Marta Minujín and her stuffed, bright hanging wall pieces that look like Fruit Stripe gum got into a pillow fight. The difference is that Balder’s gum is chewed.

Both Balder’s Pinglet and Fiber Painting abstractions appear to be dancing or blowing in the wind. They are free, and Balder found both freedom and home in the creation of her own combinations and interpretations of media that don’t stick to traditional definitions of painting or sculpture.

Emma Balder, Juggling, 2020. Fibers, graphite, acrylic, and micron on paper, 22 x 30″. Photography © Jay Marroquin; Artwork © Emma Balder

Interestingly, when asked about her main artistic inspiration or influence, Balder, without hesitation, mentioned that she is often thinking about and inspired by Catalan architect Antonio Gaudi. As a Barcelonaphile who has experienced Gaudi’s architecture in person, this resonated with me on multiple levels: bright playful colors, organic forms, structure, and the fact that architecture can be a site where art, home, and nature coalesce. Balder’s works are each like small architectures.

Through our conversation, I learned that Balder intends to generate the abstract feeling of home throughout her oeuvre. I asked her if she wouldn’t mind revealing the source of the importance of home in her work. She mentioned she moved around a few times as a child, and what she always missed most and returned to in her mind was her favorite place: the natural environment that surrounded her first house, where she would play amidst a cluster of trees, have secret meetings with friends or siblings, and carve into or decorate the tree trunks. She felt at home in nature, in these trees, more than the house itself. If you look at Balder’s Pinglets, they are formally reminiscent of horizontal slices of tree trunks.

Emma Balder, Remains 3, 2021. Recycled fabric, wool yarn, graphite, embroidery, ink, acrylic and thread on canvas, recycled fiberfill and foam filling, 30 x 42 x 3″. © Emma Balder

Balder’s commitment to the environment has also attracted the attention of large brands. She was selected in 2019 by PepsiCo as one of the three environmentally-focused artists chosen to have their artwork featured on the series of 100% recycled plastic LIFEWTR water bottles. Sweeping visuals of Balder’s Fiber Paintings can still be found on the bottles today. The series marked a moment of transition for LIFEWTR to go from using regular plastic bottles to recycled ones. While it is still not good for the environment to have single-use plastics in circulation, the massive shift of a company like Pepsi to transition their bottles from new to recycled materials is a step in the right direction. Last week I serendipitously came across Balder’s LIFEWTR bottle at JFK Airport en route to Miami, and was thrilled to have the chance to take in the visual of it with in-depth insight into Balder’s practice, rather that looking at it as an image on a product without context.

LIFEWTR Series 9.3 “The Art of Recycling”, Emma Balder, Image courtesy of the artist.

Looking ahead as Balder continues to develop her practice, she desires to focus even more intently on creating space, and inviting viewers in. “I don’t know how much longer the wall is going to serve me. I have been playing around with sculpture, and I would really like to create an immersive space where the viewer can feel like they are part of that world, and feel that sense of coming home,” she revealed. I look forward to seeing the worlds Balder has in store.

Emma Balder, Watching the World Turn, 2021. Recycled fabric, webbing, wool yarn, paracord, thread, hand embroidery, acrylic on canvas, recycled foam filling, 78 x 60 x 3”. © Emma Balder

John Torreano, “Sea Sky Gold,” 2018. Acrylic paint and gold leaf on plywood 45 x 180 inches. © John Torreano courtesy Lesley Heller Gallery.

John Torreano, “Sea Sky Gold,” 2018. Acrylic paint and gold leaf on plywood 45 x 180 inches. © John Torreano courtesy Lesley Heller Gallery. John Torreano: Dark Matters Without Time (installation view, Lesley Heller Gallery, New York, 2018). © John Torreano courtesy Lesley Heller Gallery.

John Torreano: Dark Matters Without Time (installation view, Lesley Heller Gallery, New York, 2018). © John Torreano courtesy Lesley Heller Gallery.

Iris van Herpen dress including polyurethane resin and iron fillings hand-sculpted with magnets, Autumn/Winter 2014

Iris van Herpen dress including polyurethane resin and iron fillings hand-sculpted with magnets, Autumn/Winter 2014

Gowns, Dior (left, center) and Alexander McQueen (right)

Gowns, Dior (left, center) and Alexander McQueen (right)