Above image: Installation view, Zoe Young: Still. Life. Courtesy of Gruin Gallery and domicile (n.).

This article was originally published in Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art

By Alexandra Goldman

Still. Life., a strong solo exhibition of sizeable still life paintings by Australian artist Zoe Young, opened October 15th as the third successful exhibition collaboration between Gruin Gallery, founded by formerly New York-based gallerist Emerald Gruin, and domicile (n.), an innovative East Hollywood multi-modal artist project space created by Cyrus Etemad and curator Margot Ross. Still. Life., Young’s first breakout solo exhibition in the U.S., will remain on view at domicile (n.) in LA’s Merrick Building until November 22nd , 2021.

Zoe Young and Emerald Gruin met one another while studying together at the National Arts School in Sydney over a decade ago, and have since maintained a friendship and mutual appreciation for one another’s work. Still. Life. represents a consummation of their meaningful relationship over many years.

The title of the exhibition, Still. Life., is immediately sobering. Young created all the still life paintings in this exhibition during pandemic quarantine lockdown in Australia, isolated and alone in her studio. By breaking up the two words, it poses questions and presents thoughts about these words individually. What does it mean to be still? What does it mean to be alive? What does it mean to be separated, when you’re used to being together? And, most importantly, when and how does life still go on? These reflections are all embodied in each of Young’s still life paintings.

Australia had one of the world’s strictest pandemic travel regulations, only opening its borders for the first time after twenty months this week on November 1, 2021. Young’s artistic practice frequently included portraits and other figurative imagery of people prior to the pandemic, however in lockdown, she turned to the still life, focusing on the decadence and pleasure of objects in the absence of people.

Young is a multi-year finalist of Australia’s Archibald Prize, which is considered Australia’s most prestigious award for portraiture. When there are not people around to paint, what could better express the stories of people than their things? Young’s paintings in Still. Life. are in this way imagined portraits of people, showing evidence of their tastes and existence through books, cassette tapes, food, drink, and décor without revealing their physicality.

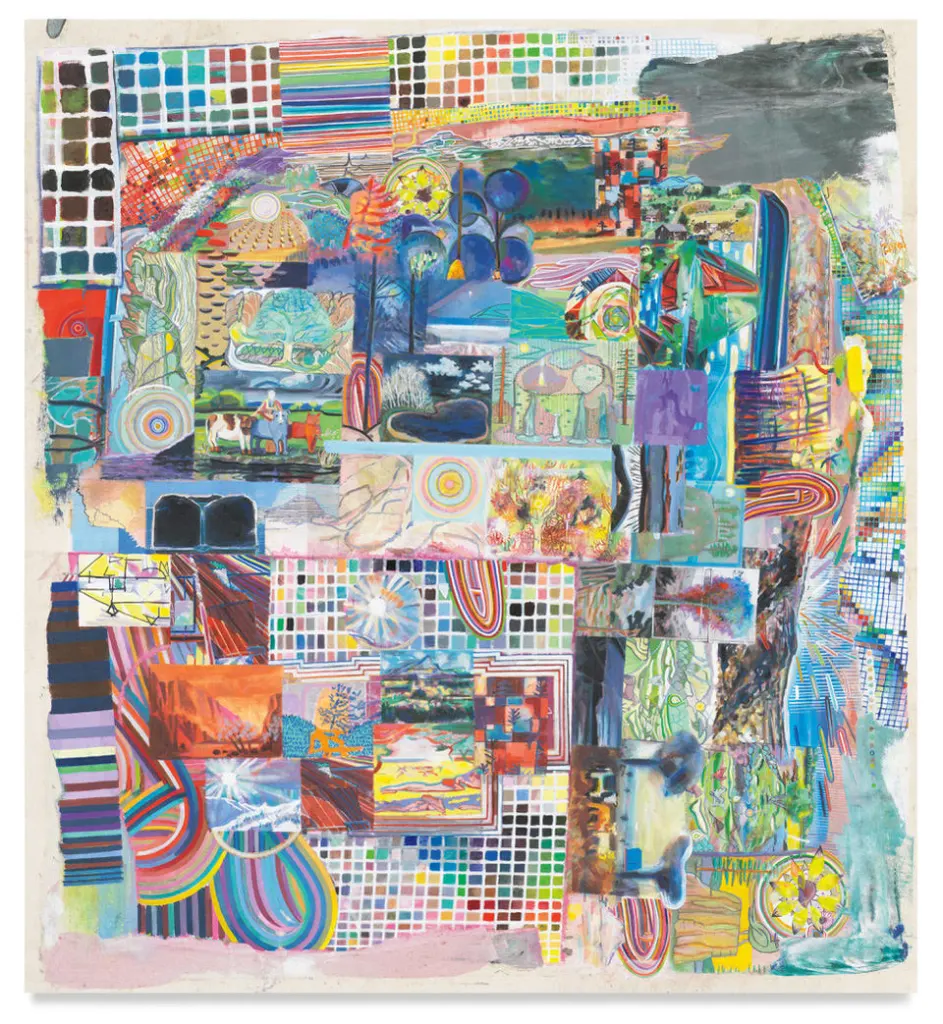

Zoe Young, Squid ink pasta for breakfast before breakfast at Tiffany’s, 2021, Acrylic on Belgian linen, 59 x 59 x 1 5/8 ” (150 x 150 x 4 cm). Courtesy of Gruin Gallery and domicile (n.).

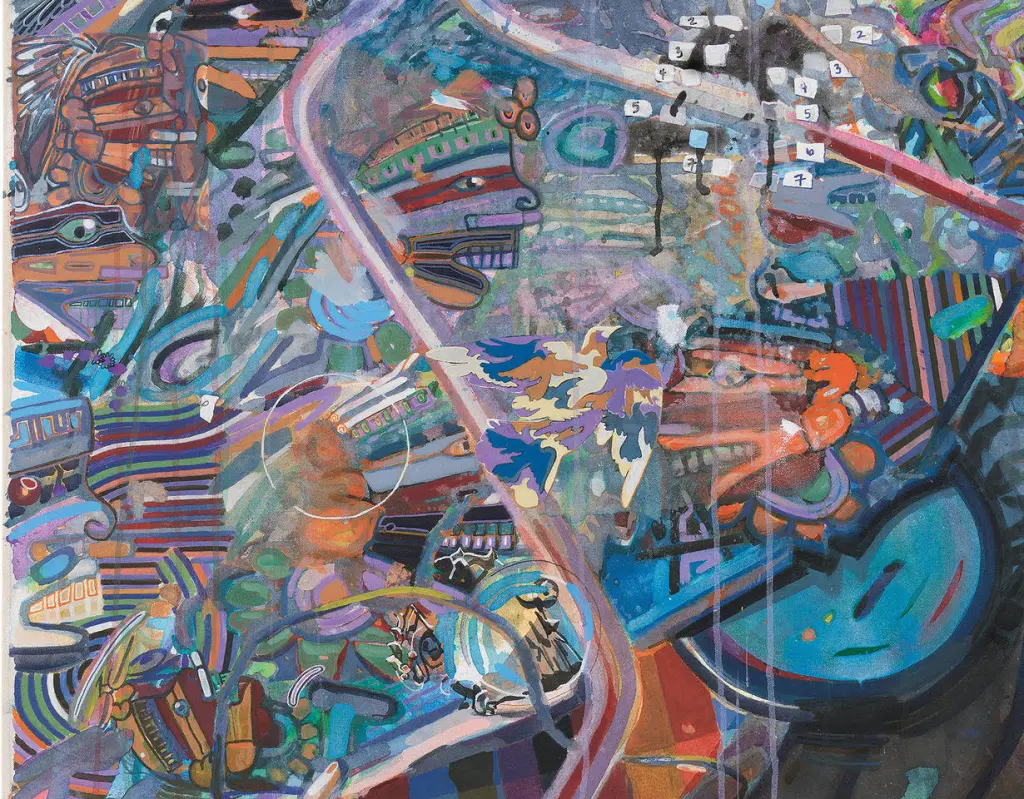

Each painting details one of Young’s imagined fantasy dinner parties in Tinseltown, which she yearned for while in solitude. The artist had never been to LA, but always dreamed of going to experience its patina, glamour, and allure. The lengthy quarantine she weathered only heightened her desire to bring these fantasies to life through her art: both of traveling, and intermingling with people in the most basic of ways. There is a unique joy that comes from clinking glasses and sharing food off of the same plates as others, evident in Young’s paintings.

Formally, the works show off the artist’s hand with generously applied paint and visible brush strokes. Young’s soft, Francophile color palette is optimistic, with what feels like dappled sunlight pouring into each scene and highlighting the architecture of her objects. Young’s style of painting is reminiscent of Matisse, Alice Neel, and Wayne Thiebaud. Some moments in the paintings reveal Young’s affinity for French culture by way of certain wines, cheeses, Louis Vuitton, perfume, and even a tiny French flag on a toothpick, while others such as fish heads and lemons recall 17th century Dutch vanitas still lives. One of my favorite moments in the exhibition is how, in the work “Chablis, Surf shacks + Olives”, 2021, Young paints the reflection of a striped tablecloth refracting within a white wine glass, demonstrating her attention to detail and technical prowess.

The paintings also evoke a cross-continental playfulness and sense of humor. Young’s scenes often pretend to feature L.A. beaches, but as many Australians may recognize, actually depict Sydney’s Bondi Beach. Nods to surf culture from both California and Australia make appearances throughout the exhibition, and in an Oscar Wildian fashion, Young paints herself into her work fusing her own name onto one of her painted book covers.

Zoe Young, Bribery and corruption over brunch, 2021, Acrylic on Belgian linen, 68 1/8 x 88 1/4 x 1 3/8 ” (173 x 224 x 3.5 cm). Courtesy of Gruin Gallery and domicile (n.).

Finally, many of the fruits in young’s still life paintings are fabulously mythological and sexual, such as pomegranates, strawberries, pears, grapefruits, and avocadoes; a possible commentary on the desire for human touch, absent for many in isolation during the pandemic. Several of these fruits also grow in gardens in both Australia and California, linking the two geographic regions. Emerald Gruin holds gardening dear to her heart as gardening was her mother’s lifelong passion and exceptional talent. Therefore the heavy presence of flowers, fruits and vegetables throughout this exhibition is additionally an important connection between artist and gallerist.

Young was deeply saddened believing for a long time that due to the continued lockdown in Australia, she would not be able to make it to her own first ever U.S. exhibition in LA. However, because of the recent opening up of Australia’s travel restrictions on November 1st, Young will finally travel to Los Angeles. In her honor, Gruin Gallery and domicile (n.) extended the exhibition and will be hosting a real Hollywood dinner party for Young in the gallery space, surrounded by her paintings, with plans to have the real dinner mirror the aesthetics in the paintings. It seems for this powerful, manifesting artist, that fantasies do come true.

Zoe Young, Still. Life. is on view at Gruin Gallery x domicile (n.) in the Merrick Building, 4859 Fountain Avenue, Los Angeles, CA, from October 15 – November 22, 2021.

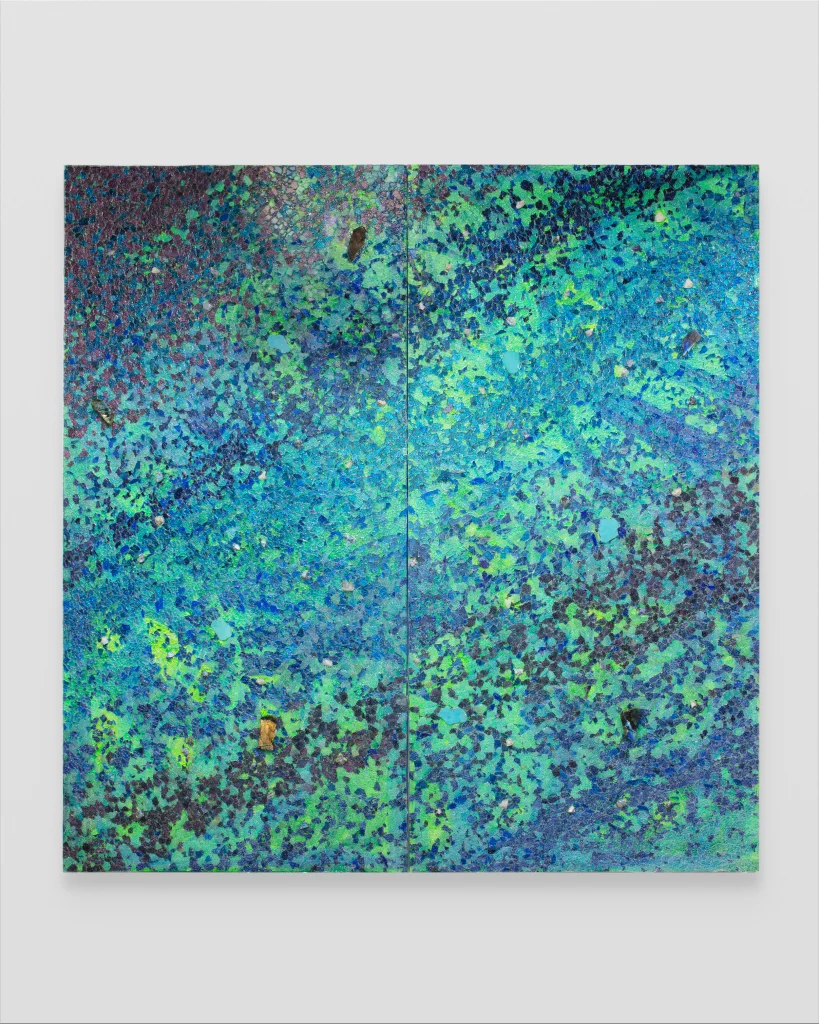

John Torreano, “Sea Sky Gold,” 2018. Acrylic paint and gold leaf on plywood 45 x 180 inches. © John Torreano courtesy Lesley Heller Gallery.

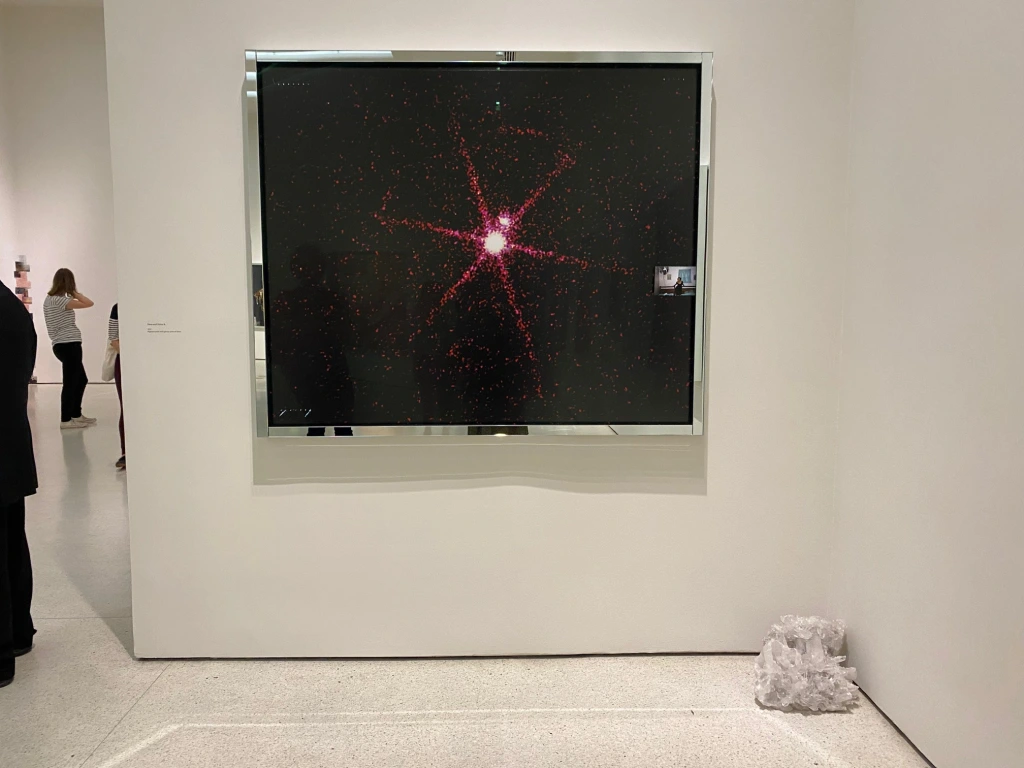

John Torreano, “Sea Sky Gold,” 2018. Acrylic paint and gold leaf on plywood 45 x 180 inches. © John Torreano courtesy Lesley Heller Gallery. John Torreano: Dark Matters Without Time (installation view, Lesley Heller Gallery, New York, 2018). © John Torreano courtesy Lesley Heller Gallery.

John Torreano: Dark Matters Without Time (installation view, Lesley Heller Gallery, New York, 2018). © John Torreano courtesy Lesley Heller Gallery.