Original article published in Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art.

The New Museum’s current show The Keeper, curated by Massimiliano Gioni, pushes the boundaries of the definition of art by exploring practices of collecting and preserving objects as the subject of a museum exhibition.

The Keeper features expansive collections of items compiled by artists, scholars, collectors and hoarders over the past century which provide viewers with opportunities to muse on how the things that people amass and safeguard speak to their identities. How does what we decide to keep reflect upon who we are? Themes of memory, struggle, loss, the need for comfort, and the passing of time also pervade the four-story exhibition.

Installation view of The Keeper, featuring a sculptural installation by Carol Bove and Carlo Scarpa, and paintings by Hilma af Klint

Installation view of The Keeper, featuring a sculptural installation by Carol Bove and Carlo Scarpa, and paintings by Hilma af Klint

Included are works like Canadian artist-curator Ydessa Hendele’sPartners “The Teddy Bear Project” (2002), which comprises more than 3,000 antique portraits of people and their teddy bears, Shinro Ohtake’s manic collaged scrapbooks (1979-2016), and Susan Hiller’s “The Last Silent Movie” (2007-2008), an audio work sounding the voices of the speakers of twenty-five extinct or dying languages.

While many of the collections of items included in the show are impressive and thought provoking, it’s not difficult, as a viewer, to wonder: Is simply compiling a quantity of something enough to call it art? Jose Falconi, postdoctoral fellow at the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University, critiques:

“Some of the pieces, most notably Ydessa Hendeles’s “Partners (The Teddy Bear Project)” are pieces which do not have much more merit than the mere act of collecting itself. An act that is, as we all know, one of the most basic tricks in the artist book: any object starts acquiring new meaning when they are collected — just as any object starts acquiring a new meaning when they are rendered in a different scale (very big, very small). In that way, The Keeper does very little to show that there is anything beyond putting into motion such a trick and conflating many different possible readings of the works gathered in it. What is, for example, the critical difference between hoarding and collecting? Is one simply the result of an impulse gone astray?

Installation view of Ydessa Hendele’s “Partners (The Teddy Bear Project)” (2002)

Supposedly the show is about showing that behind such repetitious acts there is something else lurking around, but I didn’t see it; the exhibition almost presents as mere celebration of collecting without any criticality. In other words: it suffers from what it is trying not to show.”

The answer to the question of the validity of collecting or amassing objects as art may certainly be up for debate, but one idea that seems to be paramount in understanding the value of a show like this, according to Writer and former New Museum Technician Matthew Blair, could be considering curating as the art form itself:

“The Keeper either raises the status of curating to a form of art-making, or blurs the lines between collecting and creating; between curating and art-making. The curators at The New Museum have always had an interest in mounting shows that tend to [utilize] more than just content and juxtaposition. They organize shows that put more of the onus on the curators — changing the role of curating to being the dominant mode of exhibiting.”

Therefore, in part, it could be said that it is The New Museum’s commitment to allowing for experimental curatorial practices that is one of the elements most on display in The Keeper, more so than any individual work.

Shinro Ohtake, “Scrapbooks” (1979-2016)

Shinro Ohtake, “Scrapbooks” (1979-2016)

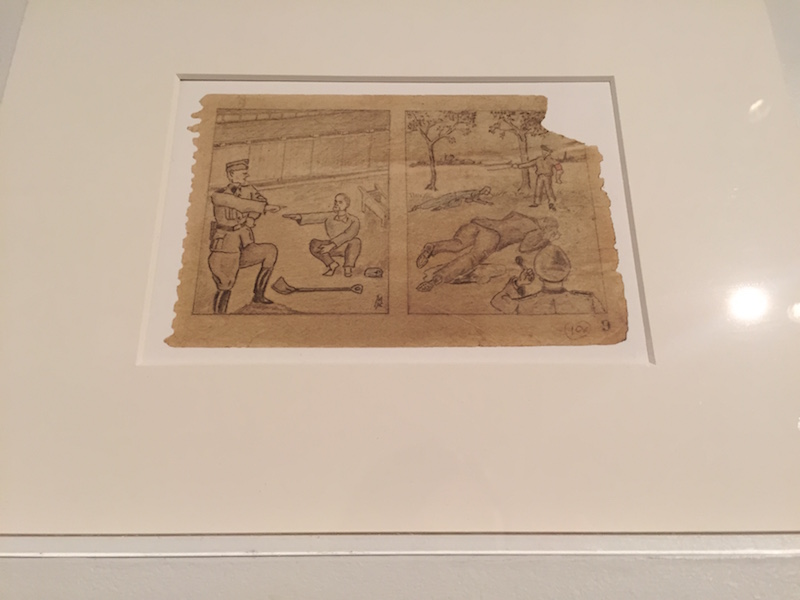

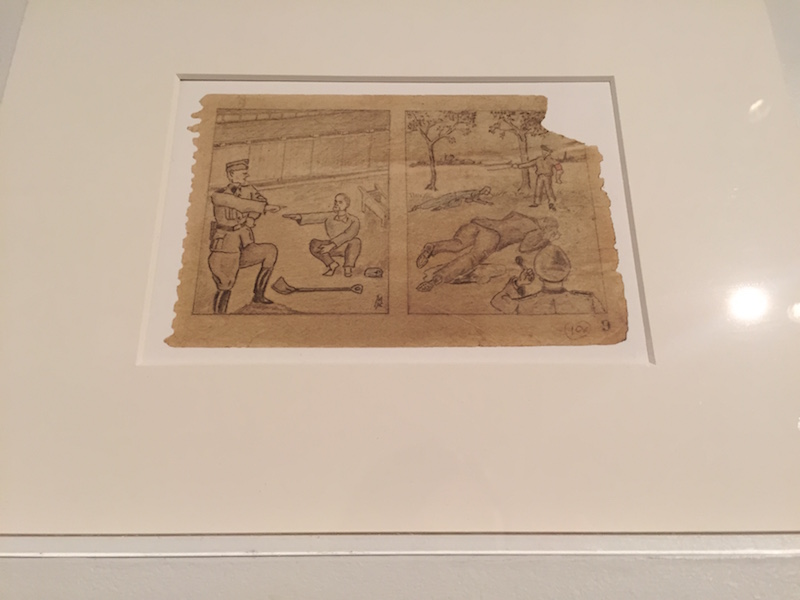

Reproduction of drawing from “The Sketchbook from Auschwitz” (original drawing included in the collection of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum), (ca. 1943)

Reproduction of drawing from “The Sketchbook from Auschwitz” (original drawing included in the collection of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum), (ca. 1943)

In the following interview, New Museum Assistant Curator Natalie Bell, who collaborated on The Keeper with Mr. Gioni provides further insight on collecting, identity, and explorations of preserving and protecting as art.

Artifactoid: From your perspective, what do you think are some of the most important things that The Keeper reveals in regards to how collecting objects relates to our identity? Are there any works that you think make some of the biggest statements? Which ones and why?

Natalie Bell: Well, almost by definition, any collection is going to reflect its collector, whether it’s merely a matter of taste or representative of a unique philosophy or set of beliefs. In this show, of course we were interested in collections that tell a story about someone’s beliefs, or an unlikely faith that certain objects and images could prove or validate an otherwise irrational or obscure idea, which is not true of everything in the exhibition, but is a significant recurring feature of many of its “keepers.” The first that comes to mind is Roger Caillois, a French theorist who collected rare stones because he believed they could reveal a shared cosmic history — which is not such a far-fetched thought if you think about the cosmic scope of geological formations. Or Wilson Bentley, who pioneered microphotography and amassed over five thousand negatives of snowflakes to prove his hypothesis that no two snowflakes are alike. But these are instances in which collecting relates to identity, if identity is understood as one’s beliefs, which is not always how we think about identity.

Oil on canvas paintings by Hilma af Klint (1914-1915)

Oil on canvas paintings by Hilma af Klint (1914-1915)

Which works make the biggest statements? An important footnote to Hilma af Klint’s luminous abstract paintings from 1914-15 is that she had stipulated, at the time of her death, that they be withheld from the public, or basically kept secret until twenty years after her death. So essentially she believed that her work, which was not so well received in her lifetime, would only be truly appreciated in the future. But maybe the most powerful work for me is one that combines a belief in a future discovery and an enormous moral imperative to bear witness, which are the drawings from an author known by the initials “MM,” which were found hidden in a bottle in the barracks near the gas chambers at Auschwitz and are among very few images made in Auschwitz that actually depict the atrocities of abuse, torture, and mass extermination. Clearly, the artist who made these knew the severity of punishment he would encounter if he was caught making these images, and he took enormous risk to document what was so impossibly horrific and was otherwise being assiduously hidden by the Nazis.

Artifactoid: In what ways is the idea of collecting and quantity important in art? When we call a collection of things art, what, in your opinion, are the effects or significances of that?

NB: Personally I don’t think quantity or collecting are virtues in themselves, but one way to think about how collecting or quantity have importance in art is that a dedicated accumulation of anything reflects someone’s passion, and maybe at times, their obsession — and alongside that, we tend to regard an artist’s zealousness or compulsiveness as a creative virtue. In a sense, this exhibition is maybe guilty of exploiting the legacy of romanticism, but the effect is perhaps visitors come away from the show with a new way of thinking about what it means to be creative. But it wasn’t a particular agenda of ours to anoint these bodies of work or collections as “art,” but rather to reflect on what is essential and universal about our emotional attachment to things, and how forming bonds with things helps us cope with our mortality.

62 consecutive annual studio portraits of Ye Jinglu, collected by photography collector Tong Bingxue, (1901-1963)

62 consecutive annual studio portraits of Ye Jinglu, collected by photography collector Tong Bingxue, (1901-1963)

Artifactoid: When considering the compiling of objects as art (which I was speaking about with Jose Falconi about), are there some important distinctions in your opinion about the practice of collecting versus hoarding?

NB: There are important distinctions, some of them arguable, but first of all I think you could call collecting a practice in the sense that it’s intentional and a collector might have to make decisions about what to acquire and what not to acquire, what’s worth keeping and what’s not worth keeping. Hoarding, on the other hand, is regarded as a pathological condition, and people who hoard have a compulsion to keep everything and suffer enormous anxiety about parting with anything. In other words, it comes down to being judicious about what you surround yourself with and having a capacity to refine one’s collection, rather than just keeping everything.

But in the framework of our thinking about the show, maybe the matter of preserving and protecting opens up something more contentious — which is that people who hoard often believe that they’re preserving the things that they keep for some future opportunity, and that their guardianship is essential. And there’s also maybe a shared psychological impulse in which amassing things can be a way of coping. But the arguable difference in my mind is that if you hoard, you’re constantly compromising your capacity to actually take good care of the things you have. That, and the fact that no one wants to become a hoarder. It’s considered a condition for good reason!

Artifactoid: There was a connection of several of the works to World War II and the Holocaust. Who decided to include multiple of those works, and why do you think that the idea of “collecting” is important related to that period in history?

NB: There are a few works that may stand out because of their relationship to the Holocaust, but I don’t think the idea of “collecting” is more related to that period in history than to others. Of course, it’s interesting generally to think about people’s relationship to material culture vis-a-vis larger historical events. It can manifest as a pragmatic approach, like how many Americans who came of age during the depression and remember the rationing of WWII have a tendency to reuse and salvage things that we might otherwise consider disposable. But this is more a trauma of poverty or scarcity that spurs collecting as a preventative measure. In other words, is my grandpa’s drawer full of golf pencils the product of his emotional attachment to these objects? Not really, considering that he has the same attitude toward saving ketchup packets from fast food restaurants.

Detail from Henrik Olesen’s “Some Gay-Lesbian Artists and/or Artists relevant to Homo-Social Culture Born between c. 1300–1870″ (2007)

Detail from Henrik Olesen’s “Some Gay-Lesbian Artists and/or Artists relevant to Homo-Social Culture Born between c. 1300–1870″ (2007)

The 387 Houses of Peter Fritz (1916-1992), Insurance Clerk from Vienna, preserved by Oliver Croy and Oliver Elser (1993-2008)

The 387 Houses of Peter Fritz (1916-1992), Insurance Clerk from Vienna, preserved by Oliver Croy and Oliver Elser (1993-2008)

But, that said, in this exhibition we weren’t so interested in the idea of collecting in a broad sense, but in something quite specific, which is a desire to preserve and protect and care for certain objects and images, so rather looking for instances where there’s a certain desire or love that’s motivating someone to action. This is a very different sort of mandate — and one that’s as subjective as it is emotional. But to return to the parts of the show that touch on the Holocaust, I think that there are potentially a lot of connections to collecting. Obviously, collecting as a form of bearing witness takes on a real urgency when there is a genocide that attempted to leave no evidence of mass exterminations, but on an emotional and psychological level, forging emotional attachments to objects is a common way of coping with the trauma, so it should be no surprise that WWII and the Holocaust stand out as something of a focal point in a show whose historical scope includes the last century.

Floors 1-3 of The Keeper will be on view at The New Museum (235 Bowery, New York, NY 10002) through Sunday, October 2nd, 2016. The fourth floor of the exhibit will be open through Sunday September 25th.