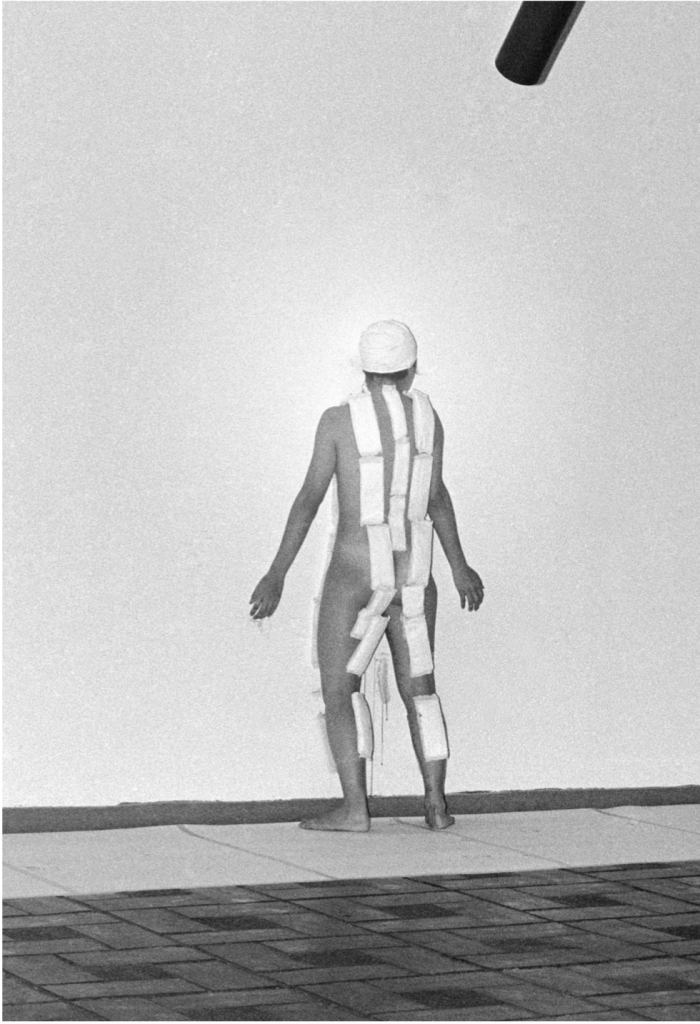

Above: Maria Evelia Marmolejo, Anónimo 1, 1981. Image courtesy of Maria Evelia Marmolejo. Photo by Fabio Arango.

This article was originally published in Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art.

By Alexandra Goldman

During weekdays Maria Evelia Marmolejo is a therapist at a child psychotherapy clinic living in Jackson Heights. She’s also a mom, and a skilled salsa dancer. When I met up with her for our interview at a cafe in her neighborhood in December 2018, I felt like she was my fun aunt. We hadn’t seen each other in over a year, but immediately reconnected. I thought, what most people at this cafe probably don’t know, is that she is one of the most badass performance artists from the ’70s and ’80s! She was giving birth in a gallery before it was cool.

Installation view: Subverting the Feminine: Latin American (Re)marks on the Female Body curated by Isabella Villanueva at Y Gallery, 2016. Photo by Alexandra Goldman.

I first met Maria Evelia when I was a Director at Y Gallery and we hosted a historical group exhibition featuring her work, curated by Isabella Villanueva and titled, Subverting the Feminine: Latin American (Re)marks on the Female Body. The show included era-marking performances, video, drawings and photography such as “Integrations in Water” by Yeni y Nan (Jennifer Hackshaw and María Luisa González), “Madre por un día” by Polvo de Gallina Negra (one of the most famous projects by the duo comprising Maris Bustamante and Monica Mayer), “Hymenoplasty” by Regina José Galindo, which won the Golden Lion award at the 2005 Venice Biennial, video and drawings by Peruvian artist Elena Tejada-Herrera, and the video “Incision” by Teresa Margolles. The caliber of historical works in that exhibition was so high; it was like a museum, yet were in a small fifth-floor lower east side gallery space. The show was in November of 2016 and I still frequently think about it to this day.

Marmolejo’s works in Subverting the Feminine were “11 de Marzo” and “Anónimo 4,” both from 1982. These two works respectively spoke to abolishing the idea of menstruation as a taboo, and the tragedy of high infant mortality in several Latin American countries.

“11 de Marzo” debuted at Galería San Diego in Bogota. For this ritual Marmolejo lined the gallery floor with an L-shaped formation of white paper. The space was lit with a blacklight, and the sound of toilet flushing played on loop in the background. She then covered her body with feminine hygiene pads, and performed a dance along the L shaped paper, using her menstrual blood to mark the floor and walls. Marmolejo states, “In this performance I emphasize the pivotal role of womanhood in the origin of life and of her civil rights in the world.”

Maria Evelia Marmolejo, 11 de Marzo, 1982. Image courtesy of Maria Evelia Marmolejo. Photo by Camilo Gómez.

Maria Evelia Marmolejo, 11 de Marzo, 1982. Image courtesy of Maria Evelia Marmolejo. Photo by Nelson Villegas.

In “Anónimo 4,” Marmolejo drew attention to the fact that when babies enter into the world, the possibility of survival and peace is not always a certainty. For this, she dug a 1.5 meter triangular pit in the ground, about equal to her height, and three smaller triangular pits around it filled with sewer water. She wrapped her entire body with plastic wrap, and entered the hole, which she filled with the placentas of all the babies born that day in hospitals near the site of the performance: Cali, Colombia and Guayaquil, Ecuador. She covered herself with the placentas, and stayed submerged in the hole, in her words, “embarking on a psychological and sociological self-exploration of the fear of being born in a society in which there is no guarantee of survival.” The experience invoked her own extreme bodily reactions such as vomiting and crying.

Maria Evelia Marmolejo, Anónimo 4, 1982. Image courtesy of Maria Evelia Marmolejo. Photo by Nelson Villegas.

Maria Evelia Marmolejo, Anónimo 4, 1982. Image courtesy of Maria Evelia Marmolejo. Photo by Nelson Villegas.

Other works by Marmolejo speak to government violence, disappeared persons, and healing Mother Earth from human-inflicted pollution and damage – especially by symbolically giving back to Earth with the body in the style of nonviolent sacrifice.

In her performance Anónimo 3, Marmolejo went to the banks of the River Cauca in Colombia, which was being severely polluted. At this site she performed a 15-minute ritual in which she formed a 10-meter spiral using limestone dust, centered around a toilet bowl. She used a vaginal wash over the bowl, adhered surgical tape to her body, and walked around spiral allowing her organic fluids and body hair ripped out with the tape to fall into the earth. Through this process she created a compost as an act of healing and forgiveness offered to the planet.

Maria Evelia Marmolejo, Anónimo 3, 1982. image courtesy of Maria Evelia Marmolejo. Photo by Nelson Villegas.

Maria Evelia Marmolejo, Anónimo 3, 1982. Image courtesy of Maria Evelia Marmolejo. Photo by Nelson Villegas.

Marmolejo is a recipient of the CIFO Achievement Award, and multiple examples of her work were included in the esteemed 2017-2018 traveling exhibition, Radical Women: Latin American Art 1960-1985, which was presented at the Hammer Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Pinacoteca de São Paolo. Below I am pleased to present an exclusive video interview with the artist:

EPILOGUE:

Now is a compelling time to revisit Marmolejo’s work, which often focuses on the fusion of the human body with the health of the planet Earth. The body and Earth are one. The power of the body, especially the feminine body, as a regenerative force, and as a power to protect Mother Earth, another feminine life giving force – our planet – that gives us the chance to exist.

In this time of Coronavirus wreaking havoc on the collective human body worldwide, there are murmurs of the virus as the planet’s retaliation against us for destroying it. Maybe not scientifically, but symbolically or spiritually.