Above: Leon Golub. “Bite Your Tongue,” 2001. Acrylic on linen, 87 x 153 in 221 x 388 cm. © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

By Jonathan Goodman

Leon Golub’s show at the Met Breuer shows him to be an allegorical artist working by way of polemics, although he cannot be faulted for cynical, self-aggrandizing intentions. Formally, his work is problematic. It is often muddy and unclear. This lack of clarity holds sway over the subject matter as well–it is not clear what unhappy situation Golub is referring to, although, generally speaking, we know the paintings are about torture and murder in Latin America, as well as racial contestations in South Africa. But we know these things from outside information; they are not available in the paintings themselves; this historical vagueness exists in contrast to the great political painting, whose outrage can always be dated to a specific event. Witness Goya’s The Third of May 1808, which documents Spanish resistance to Napoleon’s army during the Peninsular War. A similar particularity is not found in Golub’s art.

I am not trying to undermine Golub’s intentions, which are entirely honorable. Instead, I am criticizing the American penchant for casual political internationalism at a time when so much here in the States is so very wrong. The well-known and well-regarded poet Carolyn Forché traveled to El Salvador to document the political suffering there in the 1980s. Many see this as a noble attempt at social empathy, but I wish to counter that opinion by suggesting there is something unreal about the writer’s decision to concentrate on political events outside her culture. It is clear that Forché’s motives are of the highest kind, and it is also true that artists and intellectuals have often shown international solidarity with causes not directly affecting them–witness the extraordinary example of the British-born, American-based classicist Bernard Knox, who fought in both the Spanish Civil War and the Second War. But, even if we recognize the intensity of moral purpose in Forche’s poetry and Golub’s paintings, the implications of their supposedly empathic response to suffering so far away from them cannot survive in full trust.

Leon Golub. “Mr. Amok,” 1994. Ink and gouache on paper, 8 × 6 in. (20.3 × 15.2 cm). © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

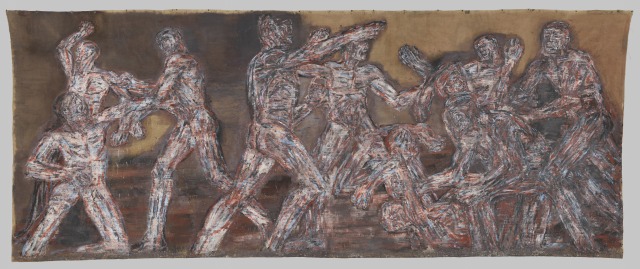

Why is this so? First, it is clear that other cultures are much better than American culture in addressing political suffering. Think of Pablo Neruda, from Chile, or Cesar Vallejo, from Peru. These artists managed to produce writing whose political effect is authentic. But, in America, while poetry readings given in opposition to the Vietnam War were certainly earnest, I cannot remember a single poem whose art rose to the level of work by the Spanish-speaking writers I mentioned. As for Golub–it goes without saying that his sympathies were genuine. But it is also true that his paintings of mercenaries don’t ring as being entirely believable. The paintings cannot be fully trusted–as good as they are!–because our manner of life here is both comfortable and socially autonomous, making it impossible to free ourselves from the trappings of privilege. Gigantomachy II (1966), a huge painting facing the elevators of the Met Breuer, continues our penchant for an imagined connectedness with trouble, on a mythic level. The word “gigantomachy” refers to the battle between the giants and Olympian gods in Greek mythology, and Golub portrays the conflict in epic style. Two groups of figures, all of them naked, fill the dark-brown background. Painted as if their skin had been flayed from their body, the combatants grip and lunge and push each other in some obscure conflict, a close-to-mad attempt to establish dominance.

Leon Golub. “Gigantomachy II,” 1966. Acrylic on linen, 9 ft. 11 1/2 in. x 24 ft. 10 1/2 in. (303.5 x 758.2 cm). © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

It is clear that Golub has painted an arresting, if murky, tale of violence by men toward other men–a theme he returns to again and again. Man’s inhumanity to man is regularly lamented, but we won’t break free of the wish to overpower our opponents. Gigantomachy II owes its power to our recognition of the conflict, but its mythic origins lie at the center of the painting. In the later works, based on actual history and places, Golub loses mythic power but gains in realism. Almost always, Golub’s audience must read the wall plaques to gain a sense of the situation being referred to. In the painting Two Black Women and a White Man (1986), two black women sit on a bench against a yellow wall. They are old and poor; both wear hats, and the woman on the left holds a cane. On the right, a vigorous white male, in his forties, looks away from the women; his gaze goes beyond the confines of the painting. He is wearing a red, short-sleeved shirt and khaki pants; as a male figure at the top of his game, he is young and powerful and seemingly indifferent to anyone’s complaint, the black women next to him included.

Leon Golub. “Two Black Women and a White Man,” 1986. Acrylic on linen, 120 x 163 inches. © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Leon Golub. “Two Black Women and a White Man,” 1986. Acrylic on linen, 120 x 163 inches. © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

The man’s overt lack of feeling is both a report and a judgment. He doesn’t give exact details, so we assume it is a work reporting on conditions where segregation, or at least profound prejudice, exists–perhaps South Africa. One might argue that not knowing the painting’s circumstances helps the artist convey the general banality of evil, but the fact remains that our inability to pinpoint the situation is disturbing enough to result in a false first step in interpreting the composition. The elements of the painting seem to be at cross purposes with each other; none of the three figures interacts with the other two. There is an implicit loss of faith from the start. Whatever the particulars of this composition may be, it is clear that the main atmosphere in which the three figures are engulfed is just shy of overt hostility.

It may be that the best art contains a realism based on experience and a more imaginative view of that experience. But what if the violence is indescribable in its extent and quality? Maybe Golub is leaning toward the allegorical because a truthful report would be so troubling as to do away with its esthetic potential. The aggression in Golub’s paintings is usually indirect–although also truthful enough in its report for his viewers to be able to imagine the aggression clearly. It is true enough that art cannot match real life, but it can embellish–and deepen–our understanding of things.

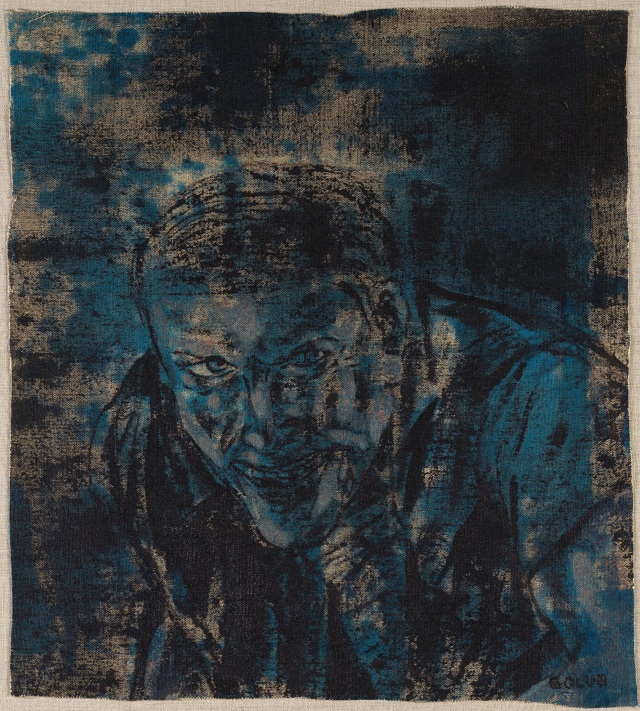

Leon Golub. “Head,” 1988. Acrylic on canvas, 21 1/2 × 19 1/2 in. (54.6 × 49.5 cm). © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Leon Golub. “Head,” 1988. Acrylic on canvas, 21 1/2 × 19 1/2 in. (54.6 × 49.5 cm). © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Golub was also interested in depicting inequalities of power in gender relations. The painting discussed implies but does not directly address gender inequalities. In Horsing Around IV (1983)–the “Horsing Around” series is based on photos of mercenaries from Africa and Central America (Golub often worked from photos)–shows a white man, with a hideous face, grinning, holding a bottle of liquor, and pulling at the white blouse of a black prostitute with short, straightened hair. The woman’s dark-brown dress ends above her thighs, and she is laughing as well, although her seeming happiness is clearly being paid for.

The prostitute sits on a bar stool, her breast revealed. Golub is making an open connection between political and sexual violence. As takes place in most of Golub’s paintings, the violence is implied rather than actual. In general, this show reveals Golub’s disgust with the behavioral excesses of power, both public and private. He is telling us that the mercenaries are more than dead souls; they are active perpetrators of malevolence. But the problem of generalization in his art remains. Violence is never generic but always specific–a particular person is doing something to a particular person. If the details are left out, the visual narrative becomes allegorical and symbolic. Despite Golub’s claim on our sympathy, true empathy is not achieved. These works portray images meant to introduce sympathy in a nearly stereotyped manner; Golub reports more than empathizes.

But reportage, a journalistic rather than an imaginative endeavor, usually results in intellectual insight rather than empathic identification. This is the problem facing all of us who have had the good luck to evade the kinds of tragedies Golub paints. It may be that good fortune, in the form of material comfort, gets in the way of our ability to sympathize with the poor and the disenfranchised. In the last painting discussed, Contemplating Pre-Columbian (no date), we see a full skeleton drawn in red chalk. The figure is in a sitting position, bent over, and with its arms bent at the elbows but also rising upward. Beneath the skeleton is a pre-Columbian skull, with a full set of teeth. The image is distraught, though there is no way of telling so. Perhaps Golub is acknowledging his own frailties: advancing age and death.

Leon Golub. “Contemplating Pre-Columbian,” ca. 2000. Oil stick and acrylic on tracing paper, 10 × 8 in. (25.4 × 20.3 cm). © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Leon Golub. “Contemplating Pre-Columbian,” ca. 2000. Oil stick and acrylic on tracing paper, 10 × 8 in. (25.4 × 20.3 cm). © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Golub feels like a major artist, but a narrow one. He is uncommonly brave to direct so much attention to worldwide injustice, as well as paying attention to the long historical ascendancy of the male gender. But even so, criticism of his political vagueness seems justified in light of our need to know who did what to whom. His paintings are sometime too generalized. Golun evoked a feeling we don’t come across much in American art–a commitment to the portrayal of injustice on an international level. If Golub’s global politics prevents him from a precise demonstration of evil, it also provides him with the space to amplify the point that, these days, morality is heavily damaged everywhere. We now find acceptable, everywhere, what was once condemned. Golub even looks at the politics of gender relations, moving from the public to the private sphere. His outrage may be slightly too generic to be absolutely convincing, but his emphasis on the consequences of violence–physical, emotional, and mental–makes him an artist of high merit.

View Leon Golub: Raw Nerve on view at the Met Breuer through May 27, 2018.

Jonathan Goodman is an art writer based in New York. For more than thirty years he has written about contemporary art for such publications as Art in America, Sculpture, and fronterad (an Internet publication based in Madrid). His special interests have been the new art of Mainland China and sculpture. He currently teaches contemporary art writing and thesis essay writing at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.